Nova schools are easily recognized.

September 28, 2002

by Trevor Harmon

Way back in the 8th grade, I had this friend who was the ultimate comic book guy. He must have had over a thousand comic books. Along with the obligatory "X-Men", "Batman", and "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles", he also kept a growing collection of Japanese graphic novels. I don't remember where he got them, but I do remember spending more than a few lunch breaks laughing with him over those silly pages. Even though the manga, as I later learned it was called, was a little too maudlin for my taste, it fascinated me. The style and stories seemed so familiar and yet so different from the traditional American comic books.

Probably because of my friend and his comic book habit, I began to take an interest in Japanese pop culture as I grew older. I found myself reading newspaper and magazine articles about robots, school bullies, Japanimation, and all the other fixtures of modern Japanese life. By the time I reached college, I knew I had to experience Japan for real. There was just one little problem: I couldn't speak Japanese!So I put off my Japan aspirations, at least for a little while.

After

college I began to have a steady job, settle down a little...I could

feel

myself turning into a suburbanite. I knew that if I ever wanted to go

to

Japan, I would have to do it fast, before I had a family and a house

tying

me down. I tried to find jobs in Japan's software industry (I majored

in computer engineering), but

every position

required some Japanese skills. Next I tried JET, but I had missed the

application

deadline by about two months. I didn't want to wait around for another

year,

so finally I turned to one of the private schools: Nova.

Following a brief interview at a Nova office in Chicago, I suddenly

got

the job, and that's when a mild panic set in. Could I really survive in

Japan

without knowing Japanese? Would I be able to save money on a Nova

salary?

What are those company apartments like? I couldn't wait until the

weekend

to call Nova. I hopped on the Internet to find some answers.

Yikes. I couldn't believe the comments I discovered. The rancor around Nova oozed through every discussion group I found. "Nova is a factory," one post said. "Nova management only cares about profit," said another. "Whatever you do, don't work for Nova," was more than typical. The messages gave the impression that Nova was some kind of Stygian sweatshop.

Now I had even more questions. Had I made a huge mistake? Was I

going

to hate my job? Is it too late to get a refund on my plane ticket? I

decided,

after some careful thought, that whatever I got out of my Nova

experience

would be exactly what I put into it, no matter what the messages said.

A

few weeks later, I packed up, said good-bye to my friends and family,

and

flew to Japan. I had passed the point of no return.

Thankfully, life with Nova wasn't nearly as bad as the discussion

groups

made it out to be. Most of the messages had grains of truth, but

overall

they seemed to come from current and former employees who had a bone to

pick

with Nova management. The strife may come from the fact that Nova hires

so

many employees straight out of college. Most new recruits have never

been

exposed to a full-time job in a corporate setting, and some may have

trouble

adjusting to the profit-oriented culture. Another explanation may be

the

nature of message posting: Diatribes pounded into the keyboard after a

bad

day at work aren't likely to show the marks of objectivity. Regardless

of

the reasons, Nova's image on the Internet has a few scars.

After a short stint with Nova (I ended my one-year contract early so

I

could enter graduate school), I was able to form my own image, one with

a

lot less vitriol than the discussion groups. It was just the sort of

balanced,

realistic view that I wish I had been able to see before I left for

Japan.

It would have made me far less nervous and fidgety about joining up

with

Nova.

It's too late for me, but prospective employees might still benefit from an objective look at life with Nova. That's what this page is all about. It's designed for anyone considering an English teaching job with Nova. (And from what I hear, the other eikaiwa, like Aeon, GEOS, and ECC, are so similar that this page might apply to them just as well.) I hope I can give enough of the good and the bad so that you can make an informed decision. Obviously, I can't promise I'll be totally unbiased, but at least I can provide details and avoid exaggerations, rather than give those blanket statements I've found in discussion groups (e.g., "Nova sucks").

But first, I should point out a few disclaimers. These are my

opinions

only; I don't represent Nova in any way. I merely worked for them as a

low-on-the-totem-pole

English teacher. I was never a trainer, head teacher, or any kind of

manager.

I guess that proves I'm neither a pro-Nova sycophant nor an anti-Nova

polemic.

There are some great reasons to work for Nova, but there are also

some

really lousy ones. The following list should help you decide whether to

take

the job.

Do work for Nova if you want a taste of the teaching life without taking a whole bite. You don't need to commit money and time to a degree in education or even basic certification. Nova, like virtually all English schools in Japan, has absolutely no requirements for certificates, experience, or previous training. All you need is a university degree: 4 years for full-time, 2 years for part-time. (I knew a guy who spent $2000 on an ESL certification course before coming to Japan...man, what a waste of money.)

Don't work for Nova if you hate bureaucracy. With over 500 branches and around 7,000 employees in Japan alone, Nova has many tentacles. You'll seldom see your boss, who will probably work in a central school, not yours. That makes the management a little impersonal, especially in the upper echelons. Your hard work may not receive much recognition. Here's an anecdote of what I mean: I knew a Nova teacher who had fallen and broken her arm. She had to take a few days off from work, but during her time off, a Nova staffer called and asked if she wanted to do overtime. They were completely ignorant of her accident! Nova management will seldom know who you really are; often you are just a number to fill a time chart in a computer database.

Do work for Nova if you like smalltalk. You'll take part in a lot of 100% brain-free conversation. Naturally, most of your students won't be able to debate the latest economic figures, new medical research, or conflict in the Middle East. Discussions will center on sports figures, pop stars, and Hollywood movies. It doesn't sound so bad - and it isn't at first - but talking about Brad Pitt's new movie every other lesson gets old fast. And, for very low-level students, you could spend forty minutes just talking about favorite foods. At the end of the day, you'll be thirsting for just about any intellectual stimulation.

Don't work for Nova if you want to go on a vacation any time soon. Nova allows both paid and unpaid time off, but never during the first six months of employment. My family came to visit during the last week of my first six months (it was unavoidable), and none of my requests for time off was approved. Finally, I simply told Nova, well ahead of time, that I could not come to work for two days of my parents' visit. My boss was not happy, of course, and he came to my branch specifically to discuss my violation of Nova policy and to tell me that a half-day's pay would come out of my salary. Take my advice: Don't even think about taking time off in your first six months.

Do work for Nova if you like kids. Nova, like its competitors, is seeing a stronger demand for kids classes. Perhaps the weak economy in Japan makes parents more eager to give their children an advantage in their future careers. Whatever the reason, Nova needs lots of kids teachers, so be prepared to teach English to rug-rats as young as three.

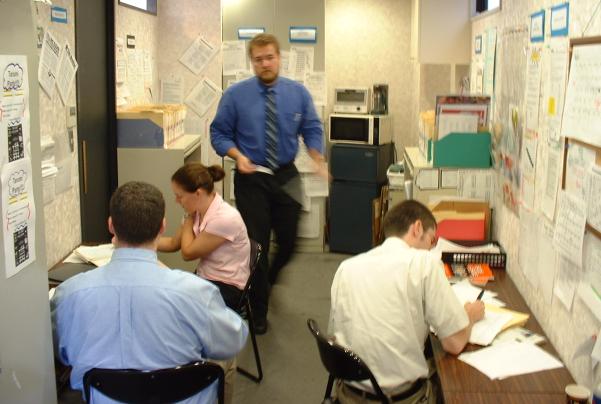

Don't work for Nova if you have claustrophobia. Want a

spacious

place to work? Try farming, because at Nova your daily view will be the

four

walls of a tiny cubicle. The teachers' lounges are microscopic, too,

with

hardly any elbow room for planning lessons. Then again, those lounges

can

also be a lot of fun. At my branch during break time, the close

quarters helped

us gossip, make jokes, or relate some horrible (or wonderful)

experience

in the last lesson. It was kind of a support group just to help each

other

survive the day.

Do work for Nova if you want to improve your "people skills". I've never been much of a conversationalist. But after just a few months teaching English, I think my speaking ability, especially at the spur of the moment, has improved a lot. I can talk more freely and more clearly, and I'm a better listener. Working at Nova demands an ability to communicate well, and if you weren't a good talker before Nova, you will be after.

Don't work for Nova if you have trouble with punctuality. Nova has a very strict policy on lateness: If you're more than ten minutes late to work, they dock you a half-day's pay. If you're late by less than ten minutes or don't call in sick soon enough, then they dock you a quarter-day. Once upon a time, a teacher at my branch was seven minutes late because her train was delayed, so she gave the staff an enchaku shomeisho (a special card that proves the train was late beyond her control). Nova refused to pay her for the lesson she worked, even though she missed just seven minutes of it.

Do work for Nova if you love hanging out with twentysomethings. Teaching English for Nova is an entry-level position, and as such, you'll find few colleagues over thirty. (The average age is 27, according to official Nova documents.) If you're older - say, forty-plus - you might have trouble fitting in to the callow atmosphere. On the other hand, going to parties after work with a bunch of Generation-X co-workers might be a great way to feel young again!

Nova is always a hot topic in any discussion group about teaching English in Japan. The typical message says something along the lines of, "Don't even think about working for Nova!" Though some complaints are certainly justified, the groups tend to evoke an image of the company that's skewed a little too far from the truth, I think, probably because most folks don't post messages unless they have something to complain about. Eventually, the Nova flaming can gather so much strength that the stories of chicanery start to sound like company policy.

I want to set the record straight on a few such misconceptions floating around the discussion groups. Below you'll find some generally accepted sentiments about Nova followed by my version of the truth. You'll find that I don't totally disagree with these "Nova myths", but I hope at least to debunk some of the broader exaggerations that continue to be made.

Imagine you accept a job offer from Nova and purchase the company's health insurance plan - known as Japan Medical Assistance (JMA) - and start work on, say, July 1. You put your nose to the grindstone, finish up your contract, and fly out of Japan on July 2 of the following year. At this point, there's no reason to pay for insurance for the full month of July, and yet Nova will make you do exactly that. JMA (a subsidiary of Nova) requires all policy holders to pay a full month's premium in whatever month the contract ends, paid holidays included. That means a Nova teacher who takes paid holidays at the end of his contract could end up paying the premium for a month during which he isn't even in Japan. (Yes, this happened to me. Try to save a few yen by timing your contract to finish up at the end of a month.)

The point of this story is that Nova does indeed find subtle ways to

extract

money from its employees, just as the discussion groups attest. Even on

the

day of orientation, your first hour will be part of a sales pitch by

Nova

staff who want you to buy a ComStation cell phone. (ComStation is also

a

Nova subsidiary.) And yet, somehow the discussion groups manage to

inflate

the problem out of proportion. Despite all the accusations, I got paid

on

time, every time, and my payslip never had a mistake. Perhaps Nova

reads

between the lines of their contract at times, but at least they always

keep

their promises.

One of these promises is access to a fully-furnished apartment. Nova

apartments

are generally more expensive than the market prices, and I believe the

company

actually makes a profit from the housing it provides to employees. So

why

in the world would a prospective employee choose a Nova apartment?

Lots of reasons. Most new Nova teachers can't speak Japanese and may never have been to Japan before. Trying to find an apartment with these handicaps would be a daunting task. (I never could have managed it on my own!) And even if you do find an apartment, you might not have the cash for "key money", a gift to the landlord that runs in the hundreds of thousands of yen. Nova doesn't ask for money up-front, so even with the higher rent, their apartment might actually be a better deal in the short term. They also pay your utility bills - up to a point - and will replace any furniture or appliances that break. (A toaster oven provided with my Nova apartment caught fire when I was heating up some spring rolls; it was replaced within a week free of charge.)

Of course, if you can read kanji well enough to decipher a Japanese apartment contract and have some extra cash on hand, then you may be in a perfect position to find your own place. If not, I suggest taking the Nova apartment deal for the first year, then hunt for your own if you decide to stay in Japan beyond that. You'll end up paying more per month, and while some folks may claim that's a Nova scam, I say it's just the cost of convenience. I doubt you'll find an English-speaking landlord and an apartment lease in English anywhere else.

This comment often pops up in the discussion groups: "Nova is the

worst

company I've ever worked for." And my first thought is, "How many

companies

have you worked for?" Like I said,

many teachers

aren't long out of college and may never have had a rigid,

40-hour-a-week

job. Combine that with the inevitable troubles adjusting to a new life

in

a foreign land, and even a minor problem could seem like a calamity.

To stay down to earth when I was a new teacher, I had to remind

myself

that teaching English at Nova is purely an entry-level position. I

wasn't

hired because I had any particular talent other than my ability to

speak

English like a native. Of course, that's a skill I share with several

hundred

million other people, so I felt pretty lucky to have the job. (Another language school interviewed me

but

eventually turned down my application.)

The point here is that Nova has little trouble replacing employees, so they don't have much incentive to bend over backward making teachers happy. At times, Nova made me feel as if I were in the military or even back in high school. Yawning, for example, is strictly prohibited in class, and teachers can't leave the building during official lesson times, even if their students have canceled. Another case in point: Let's say you have a lesson at the end of the day, but none of your students show up (yes, it does happen), so you decide to clock out five minutes before the bell and go home a little early. When your payslip arrives, you'll find that Nova refused to pay you for that last lesson and docked you an extra two for leaving work early.

Except for this strict enforcement of rules, Nova's working

conditions

always seemed fine to me. I taught at half a dozen different schools

during

my time at the company, and the classrooms were invariably clean and

comfortable,

with air conditioning cranking in the summer and plenty of toasty heat

in

the winter. The teachers, naturally, have to work in the same

conditions

as the customers, and Nova certainly wants to keep its customers happy.

And

as for the money, my travel costs always got reimbursed, my salary

always

came through on time, and the pay was on par with most other private

English

schools in Japan. I was able to send home over 100,000 yen every month.

Even if, as the discussion groups say, Nova has a nice little con game going with employee health insurance and housing, the fact is this: If you can punch in and out at the right time every day and can teach English without annoying your students, Nova will keep all of its promises and should never give you any trouble.

On my first day at my home branch, I expected to meet lots of

neophytes

like myself. Nova, after all, has a high turnover rate because, as

I

heard from a discussion group, "the teachers are unhappy and soon

quit."

Surprisingly, many of my co-workers either had renewed their contract

or

were planning to renew. Later, while working overtime at other

branches,

I occasionally met teachers with three, four, even six years of

experience

at Nova. The all-time teaching record, to my knowledge, is an

astonishing

13 years! Obviously, some people enjoy Nova life, no matter what the

discussion

groups say.

Still, a high turnover rate does exist. My guess is that nearly half

of

the employees that sign a one-year contract with Nova never finish it.

The

question is, why do they leave early? If you believe the discussion

groups,

the answer is simple: Nova is a suffocating workplace full of

intolerant students

and bloodsucking managers. Okay, some teachers leave because they just

don't

like the Nova gig anymore, but there are lots of external factors, too.

Remember

that virtually all Nova teachers are foreigners, with family, friends,

and

other roots pulling them away from Japan. If they ever have to go back

home

for some reason - maybe a parent is ill, or a friend is getting married

-

they may decide to quit Nova rather than come back to finish up a few

short

months of their contract. For others, homesickness starts to kick in,

or

maybe the timing turns out all wrong. In my case, a decision to enter

graduate

school sent me back home three months early.

At least the discussion groups and I agree on one point: No matter

when

you decide to leave Nova, sticking around for the long term probably

isn't

a great idea. Contract renewals bring only small pay raises, and more

importantly,

experience may not bring the status one would expect. From what I can

tell,

a six-year employee gets no more respect from management than a

six-month

employee.

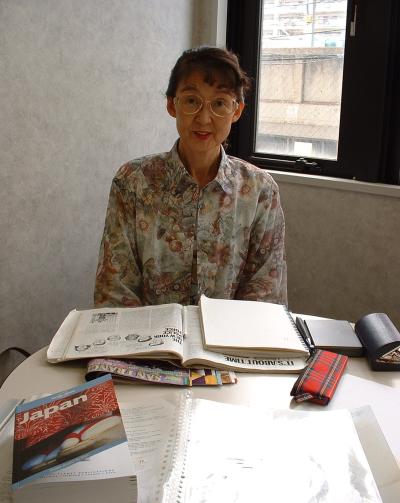

Halfway through college, I entered a student exchange program that sent me to Germany for a year. I could barely communicate with Germans until I was almost ready to leave, despite five years of previous study in the language. Part of the problem was my university's German classes; they focused heavily on literature while providing very little one-on-one conversation. Nova's classes, on the other hand, are exactly the opposite, with almost every minute focused on conversation practice. Since working with Nova, I've often wondered if my German skills would have been better had I been able to take Nova-style lessons beforehand.

My dream of a German-language Nova school in America might be described as a nightmare by others. Much of the traffic in discussion groups revolves around the poor quality of Nova's teaching methods, and some of the complaints are certainly justified. The official Quest textbook, for instance, is about twenty years old and contains lesson topics on disco dancing, sending telegrams, and the comparative sizes of East Germany and the U.S.S.R. Still, just about every teacher has at least a few favorite Quest lessons, and if those get old, Nova provides supplementary material: news articles, idiom guides, and picture books, among others. In the end, of course, it's the teacher, not the textbook, that makes the difference between a fun, effective lesson and a dry, dull one.

Another sticking point is the amount of time Nova provides for lesson planning. In the ten-minute break between periods, teachers are supposed to write down feedback for up to four students - what they did well, what they didn't, recommendations for the next teacher - and then plan the next lesson for another group of students. (And if you have to go to the bathroom...well, how fast can you run?) New teachers generally have the most trouble with short breaks - I know I did - but after a couple of months, when every lesson has been done perhaps twice or even more, a teacher can plan a lesson in less than a minute. I've seen experienced Nova teachers who spend their breaks chatting, reading magazines, even taking a smoke break outside.

The real question is, Do Nova students actually learn English, or do

these

obstacles for the teacher become obstacles for the students, too? From

my

short experience, I know students can learn English at Nova as long as

they

combine classes with home study. Several students at my branch started

at

7B or 7A (beginner levels) and are now at level 3 (almost equal to a

native

speaker). Then again, I know a couple others who started at 7C (the

lowest

level) and are still there years later, but those are the ones who

never bother

to open a textbook at home.

Despite sub-par textbooks and occasionally ill-prepared teachers,

Nova

students can learn because the essential ingredient is there: a native

English

speaker. That's more important than any fancy pedagogy because it gives

students

a chance for authentic one-on-one conversation in English. Contrary to what some may

think,

teaching experience, certification, or advanced degrees really aren't

necessary.

If the teacher can produce a fun, engaging lesson with a clear

objective,

then the students will learn English.

The side effect, unfortunately, is that brilliant teachers with

years of

experience and stacks of certificates probably won't receive any

recognition

other than a small monthly bonus in their payslip. The system is

designed

for entry-level labor, and Nova expects no special skills or talents.

(Fair

enough; most applicants have none to offer anyway.) Though students may

occasionally

present a challenge - I've been asked doozies like, "What's the

difference

between simple future tense and future perfect tense?" and "How do I

choose

between see, look at, or watch?" - overall the job requires very few

brain

waves.

So, even though Nova may care more about profit than in the quality

of

their English lessons, the system does work. I believe that any high

school

student taking Nova lessons for three years would end up with better

English

skills than a student who went through the public school's English

curriculum,

even when aided by a JET

teacher.

Besides, if the system didn't work, word of mouth would eventually stop

customers

from forking over yen in the six digits just for the privilege of Nova

lessons.

It's true that Nova's contract provides only ten paid holidays,

available

any time after your first six months of employment. It may not be much,

but

two weeks of vacation is pretty standard, at least in

America. (Maybe Nova employees from Sweden have

something

to complain about.) You can also request unpaid days off, which should

be

approved as long as you've worked at Nova for six months and your

branch isn't

too busy.

It isn't true, however, that there are zero public holidays for

teachers,

as once claimed in a discussion group. Nova does ignore certain

holidays

that other Japanese companies recognize, such as Respect-for-the-Aged

Day

(Keirou-no-hi) and Golden Week, but it shuts down completely

during

New Year's celebrations. As a result, all Nova employees get eight or

nine paid days off

around the week of New Year's Day. Add those to the ten paid days in

the contract,

plus conditional unpaid days, and you've got a decent amount of

vacation

time.

If your paid days off just aren't enough, Nova's gargantuan size can

actually

be a blessing. No matter where in Japan you work for Nova, another

branch

probably isn't far away. That makes "shift swaps" possible: You work

for somebody

on your day off; he works for you on his day off. Theoretically, you

could

work five 6-day weeks and then take a week of paid vacation. Nova also

offers

plenty of overtime shifts, as well as the chance to transfer to other

schools.

(I know a teacher who transferred to Kyoto just so he could get into

the

art scene there.) Smaller, independent private schools may have some

advantages

over Nova, but ample opportunity for shift swaps and overtime isn't one

of

them.

On a side note, it appears I have the Nova Union of Teachers to thank for my paid vacation. The union claims that employees got only five paid days off until 1995, when they forced Nova to comply with the Labor Standards Law. Incidentally, I think a union is a great idea; any company with a size and culture like Nova's should have one. Currently, though, Nova's union seems to have gone extinct. Their web page hasn't been touched in over four years, and I never heard a word about it when I was in Japan. I suppose that's a good thing; perhaps it means all of the major complaints against Nova's practices have finally been resolved. Until I hear otherwise, I'll assume no news is good news.

For me, coming up with fun icebreakers and useful lesson ideas

became more

and more difficult as the months dragged on. Recycling my bag of tricks

could

only go so far. After awhile, every one of my students had played my

silly truth-or-lie

game at least three times. I suffered occasional panic attacks when

the

bell would ring and I realized I had no idea what I was going to teach

in

the next lesson.

Mental fatigue was just one of my worries. While on break one day,

after

a long weekend that left me a little baggy-eyed, my supervisor informed

me

that a student caught me yawning in class. Apparently I hadn't mastered

the

fine art of swallowing yawns. Those who claim that Nova work is easy

probably

haven't tried to avoid yawning for eight hours on the day after a

wildly successful

karaoke party.

And believe me, you will need to hide your yawns. Nova

students

are quite vocal and don't hesitate to voice their complaints to the

Japanese

staff. But don't worry: As long as your students don't grumble about

your

lessons, your bosses will be happy and won't even bother to check up on

you.

Just remember to keep that hangar closed.

The cheerful attitude of the staff at my school always made the

days go smoothly.

Business is booming for Nova. In the last five years, the company has doubled its branches and continues to sign up customers despite a decade of economic recession in Japan. Whether this growth is due to shrewd management or merely the public's insatiable desire for English is still open for debate. But one thing is clear: Working for Nova is a great way to experience Japan for the first time. Nova will handle the nitty-gritty work of obtaining your visa and, if necessary, take care of your housing and health insurance. When you eventually arrive in Japan, you'll immediately start earning money while spending your weekends discovering the treasures this country has to offer. (I, for one, never thought I would acquire a taste for sushi!)

But before you sign that contract, get all the facts first. Visit Nova's website; call a recruiter; post questions on the discussion groups. Remember, too, that Nova isn't the only company in Japan that hires English speakers by the dozens; consider competitors like Aeon, GEOS, or ECC. And don't forget to read Introduction to Nova, the company's official policy manual. This 38-page text describes exactly how Nova deals with tardiness, sick days, and other contingencies. Ask your recruiter to provide you with a copy of the booklet and read it thoroughly. If you aren't offered access, demand it. You have a right to see it before signing because the contract forces you to follow all company policies.Once you've learned everything you can about Nova and still want to

join,

I promise it'll be worth the effort as long as you take the work

seriously.

As one anonymous poster put it, don't expect a free ride. It's a job,

not

a life-support system for your vacations to Thailand. Spend those

ten-minute

breaks planning lessons instead of complaining about Nova's greedy

tactics.

There'll be plenty of time for that over drinks at a bar with your fellow teachers.

Even if you decide you hate Nova, or that you're sick of teaching English, or you can't stand living in Japan, you probably will love your students anyway. Japanese folks are friendly and exceedingly polite, and you'll never meet another group of people so dedicated to learning your language and so interested in discovering your culture. Of course, the best way to enjoy your experience is to reciprocate and show just as much interest in the Japanese language and culture. (Not studying the language hard enough was the only regret of my Nova experience.)

I hope this document has shined some light on the joys and pitfalls of Nova life and taken some of the worry out of your decision to become an English teacher. I'm sure you'll bring back some great memories of working in Japan, just like I did.