In 1989, Peace Corps began a new program called World Wise Schools. It's like a pen-pal program, but in this case one pal is a Peace Corps Volunteer, and the other is a group of students at a school back in America. The students receive letters, photos, and sometimes video or audio tapes from the volunteers, and the students in turn send back their questions and comments. The idea is to help young people learn about life in other countries and to make all of those foreign-sounding places a little less exotic.Although I applied for the program and wrote this little piece to send to some students, there was some kind of logistical mess-up, and I never heard back from them. But it does give a pretty good picture of my life in Ghana, so instead of tossing it out, I've posted it below. Just remember that it was written for a sixth-grade audience, so don't get offended if I sound a little condescending!

My stay in Ghana began when the Peace Corps flew me and 34 other volunteers to Accra ("ah-KRAH"), the national capitol. The trip wasn't easy. Before we even got on the plane, we had to get a series of painful shots to protect us against yellow fever, hepatitis, and other diseases that are common in West Africa. The flight lasted about 18 hours, and when we finally got off the plane, we didn't have much time to relax. The Peace Corps employees drove us in vans to a nearby town to begin nine weeks of intense training that would prepare us for our two years of volunteer service in Ghana.

Ghana has more than 50 languages, so we couldn't possibly learn all of them during training. Fortunately, there are two languages that are spoken in almost every part of Ghana: Twi and English. Twi came from the Ashanti people, a powerful tribe that controlled most of what is now Ghana until the British colonized it in the nineteenth century. Because of this influence from England, the people of Ghana decided to make English their official language even after they declared independence in 1957. Today, most people speak Twi or English in addition to their native tribal language, and many speak both. Because Twi is so common, we were given two weeks of Twi classes during our training.

|

|

|

| Good morning! Good afternoon! Good evening! | Mah CHAY! Mah HA! Mah CHO! |

| How are you? | Woh HOH toe say? |

| I'm fine. And you? | Meh HOY-yay. Nah-uhn SWAY? |

| I'm also fine. | MEN-so meh HOY-yay. |

| What is your name? | Yeh FRAY ooh say? |

| My name is _______. | Yo FRAY-me ______. |

| Please | May pow-oh CHO |

| Thank you | Muh DAH see |

| Yes | Ah NAY |

| No | Day BEE |

Our trainers test our language skills as we practice bartering for

oranges, pineapples, and yams.

Language wasn't the only thing we learned at Saltpond. We also learned how Ghanaians have fun. For instance, our trainers showed us how to play the most popular musical instrument in Ghana: the drum. Almost all music in Ghana is based on the drum, and often it is the only instrument that is played during a song or a dance. Our trainers also taught us how to play Ghanaian games. My favorite is a board game called draught (pronounced "draft"), which is similar to checkers. The differences are that you have ten rows and columns on the board instead of eight, you can make jumps backwards, and the kings are much more powerful. These new rules make draught a bit more complicated than checkers but also a lot more fun. It's certainly not easy to master-I've been playing draught since I came to Ghana, yet I still lose most games to kids half my age.

A traditional drumming-and-dancing ceremony.

A fundamental part of our training began during our second week in Ghana. It's called "Homestay". As the name implies, we stayed at the home of a Ghanaian family for two weeks. When classes were over at the end of each day, we left the training site and went to our Homestays, where we ate supper and spent the night, then we returned for more classes the following day. My Homestay was with Ato Johnston, a young bachelor who teaches math and social studies at a nearby Junior Secondary School (the Ghanaian equivalent of a middle school or junior high school). Although Ato and I were the only people at his house, we were never lonely-his two dogs, Victory and Glory, and his cat, Understanding, were always around for companionship. Actually, I think Ato's pets were more interested in eating our leftover food than in keeping us company. That's not surprising; Ato's a fantastic cook. His best dishes are jollof rice, which is rice boiled in tomatoes and hot pepper, and fufu. Fufu is by far the most popular dish in Ghana, and most people eat it several times each week. It's made from boiled cassava (a starchy tuber kind of like a potato) and plantain (like an oversized banana but not as sweet). The ingredients are mixed together and pounded with a wooden mallet until they look like a smooth, shiny ball of mashed potatoes. The ball is served in a big bowl filled with a spicy, oily sauce made from palm nut oil.

Ato and his girlfriend, Eunice, pound boiled cassava into fufu.

Ato enjoys fufu with palm nut soup.

After supper each night, I would talk with Ato and sometimes listen to the Ghanaian news on the radio. Eventually my eyes would become heavy, so I would say good-night to Ato, go to my room, and read a book until I fell asleep. During the two weeks of my Homestay, Ato and I became good friends, and he promised to visit me before I return to America. As we said our good-byes, I gave him two gifts to thank him for his hospitality: a picture book filled with snapshots of Kansas City and a large bottle of "K.C. Masterpiece" barbecue sauce.

Even when Homestay was over, we still had six more weeks to go in our training. I began to get a little nervous at this point because we were about to find out where in Ghana we would be placed. Some volunteers would be placed in a town by the ocean, and some would be placed in the savannas of the north; some would live in a big city, while others would stay in a small village with no electricity. The suspense grew until the night of the big "Site Placement" ceremony in which each volunteer's future home would be announced. One by one, the training director called out a name and, when the volunteer stepped forward, she would announce the site and give the volunteer a pin to put on a wall-sized map of Ghana, marking the site's location. Name after name was called, and I was getting more and more anxious. Eventually, 34 names had been called-mine was the only one left! The crowd soon realized that I was the last one, and everyone started chanting my name. With an overly dramatic voice, the training director slowly bellowed, "Trevor Harmon... Tumu, Upper West Region!" bringing a roar of applause from the crowd.

The suspense was over. Tumu ("too-MOO"), a strange town in a foreign land, would be my home for the next two years. The only information I had on Tumu was its region: the Upper West, the poorest and least populated of Ghana's ten regions. (The others are Greater Accra, Central, Eastern, Western, Ashanti, Volta, Brong-Ahafo, Northern, and Upper East. Together, they are Ghana's equivalent to America's 50 states.) I wanted to learn more about Tumu, but I would have to wait. My training was not yet over.

The next step was to sharpen my language skills. I had already mastered the basics of Twi, but now that my trainers knew I would be living in the Upper West, they switched my lessons to Dagaare ("dah-GAR-ee"), the most common tribal tongue in that region. My Dagaare classes would last until the end of training-a total of five weeks-and I slowly grew more comfortable with the language. Soon I was using Dagaare to greet and introduce myself, just as I could in Twi, but now I could also bargain for food and cloth at the market, ask for directions, and tell bus drivers where I am going and where I need to get off. The lessons were tough, and I often heard myself mixing Twi words with Dagaare phrases. Once, I even dozed off during class, and my instructor had to wake me up. It wasn't because I was bored; it was because the classes were scheduled in late afternoon-the hottest, sleepiest part of the day-and I was already tired from the morning's work.

Our mornings were now filled with Model School, a three-week part of Peace Corps training that gives us teaching practice. Every morning after breakfast, we would meet at a nearby school with Ghanaian students who had come from in and around Saltpond. Ghana's public schools were on semester vacation at the time, so the Model School was like a free summer school for the students. For us, it was a chance to gain some brief experience teaching in the Ghanaian school system. The Model School wasn't a real school, of course, but our trainers did everything possible to make it real: The students wore uniforms and had a general assembly each morning; we graded their homework and final exams; and we even had a mock graduation when the three weeks were over. Since Ghana's official language is English, all public schools are based completely on the English language-the teachers teach in English, the textbooks are in English, and the students are expected to be fluent in English. Naturally, that made Model School easier for me because I didn't have to teach in Twi, Dagaare, or some other language new to me. Yet even without a language barrier, I still found Model School demanding. I had never taught before, and I always got nervous before each period, as if I were about to give a speech on live national television. And somehow, I always managed to cover my shirt and pants with chalk dust by the end of my lessons. By the third week, though, I was beginning to get the hang of it. I learned how to speak slowly and clearly and to use British vocabulary (for instance, "marks" instead of "grades", "rubbish bin" instead of "trash can", "football" instead of "soccer"). I also discovered the boredom of grading papers and the exhaustion of standing, walking, and talking for an hour and twenty minutes straight. But I also witnessed the smiles on my students' faces when they solved math problems correctly, and I knew they were learning something even during the short time when I was their teacher. And then, at the end of the very last lesson of the very last day, I looked around to see all of the chalk on the chalkboard and none on my clothes.

A crowd gathers at the Tumu bus station, where I organized a Saturday

morning pancake breakfast as a fundraiser for the school.

With Model School complete, my training had come to an end. The Peace Corps staff organized a lavish ceremony for us in Saltpond and invited all of the Homestay families, some Ghanaian chiefs, and a few government officials. Speeches were made; certificates were given; refreshments were served. For the final part of the ceremony, a few of the Peace Corps volunteers presented a speech or a play in the language that they had studied. One of the Dagaare students and I sang a traditional Ghanaian song while I played along on a wooden xylophone. (I was so nervous that I hit the wrong notes at first, and we had to start over from the beginning!) The next day, we packed our things, said good-bye to each other, and boarded a bus to take us out of Saltpond and to our new homes.

Two days later, I arrived in Tumu. The moment I stepped off the bus, a young boy wearing bright yellow flip-flops appeared in front of me and asked to carry my bags. "OK," I said, feeling the weight of my three backpacks grinding into my shoulders and palms. I handed him the lightest one, and we hiked down the tarred main street toward Tumu Secondary/Technical School, where I would soon begin teaching.

The school and the bus station were on opposite sides of town, and I watched the scenery carefully as we walked. Tumu, I decided, is bigger than a village but smaller than a town. Yes, it has a bus station, a bank, a post office, several restaurants, and even telephones and electricity (which had been installed just seven years ago, I later learned.) You won't find such luxuries in any village in Ghana, so Tumu certainly is not a village. But Tumu isn't quite a town, either-it's just too poor. Our bus station is a field of dirt where the busses park. Our restaurants are four cement walls (no roof) that contain some plastic patio chairs and a woman who will bring you banku or jollof rice, including goat meat if you're lucky enough to arrive before the lunchtime crowd. Even our gas station isn't really a gas station. It's just a rusty metal tank, about as big as a refrigerator, with the word "PETROL" scribbled on it in white paint. With all these places put together, they give Tumu the feel of a small sleepy town, where the season is always summer and nobody has to be anywhere at any particular time.

My home in Tumu: a luxury bungalow with two bedrooms, full bath,

and backyard chicken coop.

After what was probably fifteen minutes (but felt a lot longer because of my bags), we arrived at the school and made our way to the bungalow that the school had reserved for me. I dumped my stuff on the floor, pulled out a pocketsize package of Oreos that I had bought during the bus trip, and gave them to my flip-flopped friend as a thank you. He left, and I was free to relax and explore my new house.

Like almost every other Ghanaian house, it's a one-story structure with a cement floor, cement walls, and a roof made of corrugated metal sheets. The windows are pretty standard: a grid of thick metal wires to keep the burglars out, followed by a layer of mosquito netting and a row of "louvers", which are horizontal panes of glass that can be rotated by a little lever to let air in or keep rain out. The cracks and stains on the cement floors aren't too attractive, but each wall is painted brightly in one of three colors: turquoise, yellow, or pink. The kitchen has a cement sink, but there's no running water anywhere in the house. As for the toilet, it's just an empty room with a small hole in the floor that leads to a deep pit. I wasn't too thrilled about that, especially when I discovered the smell and the cockroaches. But at least the house is wired for electricity, so every room has a light, and the living room and the two bedrooms even have ceiling fans.

One of the bedrooms is for me; the other is for Ed, a VSO volunteer from England. (VSO is just like the Peace Corps, but it's for people who live in Britain, Canada, or the Netherlands.) He arrived in Tumu about two weeks after I did, and he's assigned to teach chemistry and general science. He can't stand Ghanaian food, and VSO gave him only a little bit of language training, so he's had a tough time adjusting to life here. But he works hard as a teacher, and after a year of living together, we've become good friends.

Because school didn't start until a week after I arrived, I had a chance to ride my bicycle around town. (Peace Corps provides all volunteers with a rugged, fat-tired mountain bike.) The first thing I noticed was the little kids-or rather, they noticed me. A white person is so rare in Africa that children often get excited when they see one, as if they've spotted an alien from outer space. Even from a distance, they will usually smile, point, and chant, "White man, white man, white man!" in their native language as soon as they see any white person. Sisaala ("sis-AH-luh") is the native language in Tumu, so the children here shout "Foli, foli, foli!" ("FOH-lee") whenever they see me. If I happen to steer my bike in their direction, they usually get scared and run away. Sometimes the brave ones will stand still and stare at me in silence when I come close, not really knowing what to do. I try to talk to them, but I can't speak Sisaala and they haven't learned English yet, so eventually I just ride away. A few times, I've walked past children on the street who suddenly burst into tears and scream for their mothers. They probably think I have some horrible disease that has turned my skin white and my eyes blue.

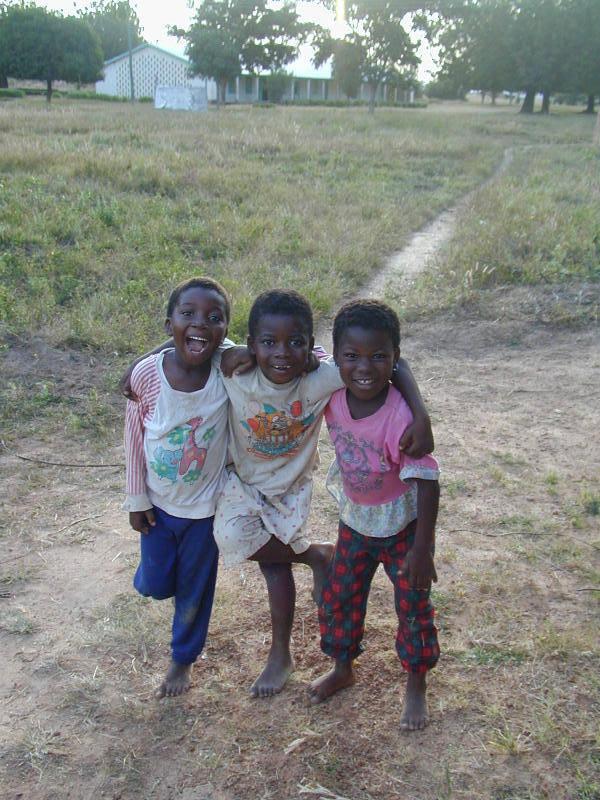

These children, who often play at the Sec/Tech campus, have learned

never to call me "foli".

Like all communities, Tumu has its nice parts and its not-so-nice parts. One of the nicest parts is a large green pond with a little rock island, which makes a beautiful scene when the sun goes down and turns the water silvery. (I've heard from very reliable sources that an alligator lives in the pond, but I have yet to see it.) There's also a nice restaurant that serves roasted chicken with onions under a thatched grass roof. And though it's hard to find, there's a little store across from the bus station that sells FanIce-Ghanaian ice cream served in a small plastic bag. No spoon necessary, you just rip off a corner of the bag with your teeth and start sucking. It's great! As for the not-so-nice parts, Tumu doesn't really smell very good. Many families here own a small collection of chickens, guinea fowl (looks like a cross between a chicken and a turkey), goats, pigs, and sheep that they raise for food. The owners never build pens, so their animals just wander around town, lying in dirt and pooping everywhere. To make matters worse, there are no trashcans in Tumu, so everyone throws their old FanIce bags and whatever else into the gutters in the street. If they have a lot of trash to throw out, they take it to the Tumu dump, which is right in the center of town. I always have to hold my nose whenever I ride by. The smells of Tumu might not be the best in the world, but that's not what's important. It's the people that count, and the people here are some of the friendliest I've ever met. They're always ready to greet me and ask how I'm doing. And there are certain folks I depend on just to make it through the week. For example, there are no washing machines anywhere in Ghana-they're just too expensive. Everyone here washes their clothes by hand in a bucket. I've tried washing my clothes by hand, but I'm probably the worst washer in the Upper West. Somehow my clothes always end up feeling soapy yet smelling dirty. And of course, it's hard work; my shoulders and back start to ache after just fifteen minutes of washing. Fortunately, one of my neighbors comes to the rescue. Natalia, an elderly Dagaare woman who lives nearby, appears at my door every Saturday morning, takes my dirty clothes and a little bit of money, and returns with a clean, dry load of wash. Prudence, a young Sisaala woman who lives on the other side of town, also helps me out. Every week, I give her money to buy ingredients, plus some extra money to keep for herself, and she arrives Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evenings to cook me a Ghanaian meal. Not only do I get to enjoy hot, spicy, homemade food, but with the time I save cooking, I can plan more lessons, grade more homework, or just relax in peace after a busy day.

The schools here don't have enough money to hire custodians, so the students must do all of the cleaning. For the first three days of each term, no one goes to class. Instead, the students pick up litter from the assembly ground, sweep goat dung off the steps, cut down the grass-which can grow up to six feet high during the vacation-with a machete, since lawnmowers are too expensive for anyone in Ghana to afford.

Once the campus has been cleaned, the normal routine begins. Every Monday and Friday at 7:45AM is reserved for a school-wide assembly, where the students form columns and stand in silent attention. Then the school's senior prefect (kind of like a class president) leads the group in singing the national anthem, reciting the national pledge, and saying the Lord's Prayer. After that, the headmaster-that's the British word for principal-addresses the school, giving any announcements that need to be said. Finally, the assembly is over, and the students head for the classrooms, ready (more or less) to face another new day at school.

In American high schools, each teacher has his or her own classroom, and the students rotate among them when the bell rings. But in Ghana, there aren't enough teachers and classrooms to go around, so instead, the students stay in the same classroom all day, and the teachers come to them. On Thursday, for example, I teach math to a group of second year students at 9:45, but at 11:05 I end the lesson and walk to one of the third year classrooms to teach physics. As soon as I enter, the class prefect cries, "Class up!" and everyone stands up. "Greet!" barks the prefect, and the class chants in unison, "Good morning, Master!" or "Good afternoon, Master!" as the case may be. (Master is the British word for teacher.) The ritual isn't out of some special respect they have for me; they have to greet every teacher formally at the beginning of the period. If they refuse to stand and greet, they'll be punished.

After using a Slinky to demonstrate sine waves, I show the students

how to play with it, since they had never seen one before.

Punishment is almost always some kind of manual labor. During the wet season, when the grass on campus is high and thick, a punished student will be sent to chop down grass with a machete. In the dry season, when all the grass has died off, the teacher will make the student fetch water from the nearest bore hole (a type of deep-water well that provides all of Tumu's water) to his house. Or, if the student did something especially bad, the punishment will be sweaty work that's not only exhausting but also pointless. I know one teacher whose students locked him in the science lab, and for punishment, they had to fill two buckets with rocks, carry them to the other side of campus and back, then dump the rocks out-ten times over!

Students can be punished for almost anything: being late to school, speaking their native language instead of English, or even wearing the wrong shoes. If a student comes to school wearing flip-flops instead of sandals or proper shoes, he'll have to kneel in front of the whole student body during the morning assembly. In addition to correct footwear, every student must come to school wearing the standard uniform: a light-blue button-down shirt and brown shorts for the boys; a light-blue dress for the girls.

The coastal city of Elmina, green and warm all year round, is a

home for many fishermen and their giant wooden canoes.

The northern part of Ghana, where I stay, is a little different. It's

further from the Atlantic ocean and closer to the Sahara desert, so the dry

season has much more of an effect on us. (Ghana has two seasons, not four:

the wet season, when it rains at least every week, and the dry season, when

it hardly rains at all.) Starting around May, the rains come and the ground

suddenly turns bright green, like a well-kept golf course. As the months

go by, the grass grows higher and higher until it rises above my head. Then,

in December, a period called the harmattan ("har-mah-TAHN") sets in and brings

heavy winds from the Sahara, kicking up dust and turning the whole sky hazy.

It actually gets cold enough to wear a sweater during this time-at night,

at least. By January, the rains have completely stopped, and the grass dies

off and turns brown. The only green that you see is the leaves on the trees.

The temperature rises, too, and can reach 120°F in the shade, forcing

many people to sleep outdoors. The lack of rain prevents palm trees from

growing in the North, but there are plenty of mango trees everywhere. When

March rolls around, mango season comes with it, and you can hardly walk through

Tumu without tripping over a mango seed (like a peach pit, but twice as big)

that somebody had tossed away.

Religion is a big part of life in Ghana, much more than in America. And I don't mean that people here go to church more often--it's more fundamental than that. If you're talking to a Ghanaian farmer and say, "It looks like the rain will come," a common response might be, "Yes, by God's grace, the rain will help our crops this year." As another example, if your colleague is on vacation and you ask your boss when she will return, he might say something like, "God willing, she will arrive tomorrow."

In the same way that Ghanaians flavor their speech with references to God, entreprenuers in Ghana rely on their spirituality when naming their business ventures. Click here for a small collection of the names of stores, shops, and bars that you will find along the roads in Ghana.